Let us see how the Laplace transform is used for differential equations. First let us try to find the Laplace transform of a function that is a derivative. Suppose \(g(t)\) is a differentiable function of exponential order, that is, \(|g(t)| \leq Me^

| \(f(t)\) | \(\mathcal\=F(s)\) |

|---|---|

| \(g'(t)\) | \(sG(s)-g(0)\) |

| \(g''(t)\) | \(s^2G(s)-sg(0)-g'(0)\) |

| \(g'''(t)\) | \(s^3G(s)-s^2g(0)-sg'(0)-g''(0)\) |

Notice that the Laplace transform turns differentiation into multiplication by \(s\). Let us see how to apply this fact to differential equations.

Take the equation \[ x''(t) + x(t) = \cos (2t),~~~~~~~ x(0)=0, ~~~~~~~ x'(0)=1. \nonumber \] We will take the Laplace transform of both sides. By \(X(s)\) we will, as usual, denote the Laplace transform of \(x(t)\). \[\begin

The procedure for linear constant coefficient equations is as follows. We take an ordinary differential equation in the time variable \(t\). We apply the Laplace transform to transform the equation into an algebraic (non differential) equation in the frequency domain. All the \(x(t)\), \(x'(t)\), \(x''(t)\), and so on, will be converted to \(X(s)\), \(sX(s)-x(0)\), \(s^2X(s) - sx(0) - x'(0)\), and so on. We solve the equation for \(X(s)\). Then taking the inverse transform, if possible, we find \(x(t)\). It should be noted that since not every function has a Laplace transform, not every equation can be solved in this manner. Also if the equation is not a linear constant coefficient ODE, then by applying the Laplace transform we may not obtain an algebraic equation.

axis and the horizontal right directional ray starting at (0,1)" />

axis and the horizontal right directional ray starting at (0,1)" />

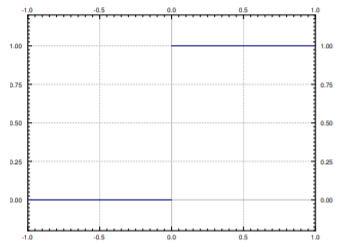

Before we move on to more general equations than those we could solve before, we want to consider the Heaviside function. See Figure \(\PageIndex<1>\) for the graph. \[u(t)=\left\< \begin 0 & >t<0, \\ 1 & >t \geq 0. \end \right. \nonumber \] This function is useful for putting together functions, or cutting functions off. Most commonly it is used as \(u(t-a)\) for some constant \(a\). This just shifts the graph to the right by \(a\). That is, it is a function that is 0 when \(

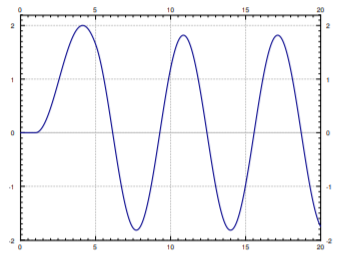

Suppose that the forcing function is not periodic. For example, suppose that we had a mass-spring system \[ x''(t) + x(t) = f(t), $$ x(0) = 0,$$ x'(0) = 0, \nonumber \] where \(f(t)=1\) if \(1 \le t < 5\) and zero otherwise. We could imagine a mass-spring system, where a rocket is fired for 4 seconds starting at \(t=1\). Or perhaps an RLC circuit, where the voltage is raised at a constant rate for 4 seconds starting at \(t=1\), and then held steady again starting at \(t=5\). We can write \(f(t) = u(t-1) - u(t-5)\). We transform the equation and we plug in the initial conditions as before to obtain \[ s^2X(s) + X(s) = \dfrac>-\dfrac>. \nonumber \] We solve for \(X(s)\) to obtain \[ X(s) = \dfrac> - \dfrac>. \nonumber \] We leave it as an exercise to the reader to show that \[ \mathcal^ \left\< \dfrac \right\> =1 - \cos t. \nonumber \] In other words \(\mathcal\ = \frac\). So using \(\eqref\) we find \[ \mathcal^\left\<\frac>\right\>=\mathcal^\\mathcal\ \>=(1-\cos(t-1))u(t-1). \nonumber \] Similarly \[ \mathcal^\left\<\frac>\right\>=\mathcal^\\mathcal\ \>=(1-\cos(t-5))u(t-5). \nonumber \] Hence, the solution is \[ x(t) = \left( 1 - \cos (t-1) \right) u(t-1) - \left(1-\cos (t-5) \right) u(t-5). \nonumber \] The plot of this solution is given in Figure \(\PageIndex\).

Laplace transform leads to the following useful concept for studying the steady state behavior of a linear system. Suppose we have an equation of the form \[ Lx = f(t), \nonumber \] where \(L\) is a linear constant coefficient differential operator. Then \(f(t)\) is usually thought of as input of the system and \(x(t)\) is thought of as the output of the system. For example, for a mass-spring system the input is the forcing function and output is the behavior of the mass. We would like to have an convenient way to study the behavior of the system for different inputs. Let us suppose that all the initial conditions are zero and take the Laplace transform of the equation, we obtain the equation \[ A(s)X(s) = F(s). \nonumber \] Solving for the ratio \(\frac\) we obtain the so-called transfer function \(H(s)=\frac\). \[ H(s) = \dfrac \nonumber \] In other words, \(X(s) = H(s)F(s)\). We obtain an algebraic dependence of the output of the system based on the input. We can now easily study the steady state behavior of the system given different inputs by simply multiplying by the transfer function.

Given \(x''+ \omega_0^2x=f(t)\), let us find the transfer function (assuming the initial conditions are zero). First, we take the Laplace transform of the equation. \[ s^2X(s)+\omega_0^2X(s)=F(s). \nonumber \] Now we solve for the transfer function \(\frac\). \[H(s)= \frac= \frac. \nonumber \] Let us see how to use the transfer function. Suppose we have the constant input \(f(t)=1\). Hence \(F(s)=\frac\), and \[X(s)= H(s)F(s)= \frac\frac. \nonumber \] Taking the inverse Laplace transform of \(X(s)\) we obtain \[x(t)=\frac<1-\cos(\omega_0 t)>< \omega_0^2>. \nonumber \]

A feature of Laplace transforms is that it is also able to easily deal with integral equations. That is, equations in which integrals rather than derivatives of functions appear. The basic property, which can be proved by applying the definition and doing integration by parts, is \[ \mathcal

To compute \( \mathcal

An equation containing an integral of the unknown function is called an integral equation. For example, take \[ t^2 = \int _0^t e^x(\tau)\, d\tau \nonumber \] where we wish to solve for \(x(t)\). We apply the Laplace transform and the shifting property to get \[ \dfrac = \dfrac \mathcal \ < e^tx(t)\>= \dfracX(s-1), \nonumber \] where \(X(s) = \mathcal \\). Thus \[ X(s-1) = \dfrac\quad\text\quad X(s) = \dfrac. \nonumber \] We use the shifting property again to get \[ x(t) = 2e^t. \nonumber \]

This page titled 6.2: Transforms of derivatives and ODEs is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Jiří Lebl via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.